The Stairs

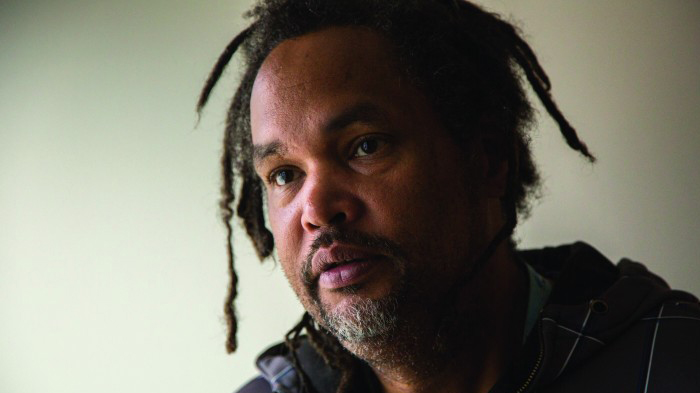

The title of Hugh Gibson’s new documentary The Stairs refers to a stairwell that once served as a makeshift living space for Martin Thompson, a habitual drug user who’s diligently pulled himself back from the brink of oblivion. “Sit down in my living room,” he says with the same excitable cheerfulness that marks most of his pronouncements. Later in the film, Martin—Marty to his friends—will share a self-penned song about his one-time home. The gist of the performance is that he has literally and figuratively moved away from the stairs, but there’s a defiance in Marty’s voice that’s much closer to pride than it is to shame. This is a man with no illusions about the realities and contingencies of his life or those of the people around him. (Read the POV review of The Stairs here.)

“The stairs were always important,” says Gibson. The director (who, in the interest of full disclosure, is one of my oldest friends dating back to junior high school) says that the scene with Marty on the stairs was one of the first things he shot, and that from then on, he was keenly aware of the location’s metaphorical possibilities. “The thing about the stairs,” he says, “is that you never know if you’re up or down, or how far you have to go. And throughout the film, we see that all of the people change places on the staircase.”

The Stairs began as a series of educational videos commissioned by a Toronto Public Health harm reduction programme located in Regent Park, an area that has undergone massive redevelopment over the past six years. The group’s mandate includes supplying users with safe injection tools and sites, as well as supplying counselling and forms of mobile outreach, but despite its sterling reputation within the community, the programme was under fire in 2011. “It was a very different political climate,” says Gibson. “Rob Ford had just come into office, and he was opposed to these sorts of programmes. The health centre there was sort of under attack, and they felt like they needed to show the city why they were valuable. They wanted to show people what drug users are actually like, and what people who work in the sex trade are actually like. And so what started as a corporate job turned into something much more personal.”

Gibson spent a huge amount of time with the people who ran the programme and the users who came by every day for supplies and conversation. He saw that there was significant overlap between the two cohorts. Part of the impetus for turning The Stairs into a feature was to more thoroughly document that symbiotic dynamic. He also senses that many of the people he met were craving an outlet to tell their stories. “Over time, as I got to know the people, they came to trust me. I think the fact that I was non-judgmental…they respected that.” At the same time, figuring out how to select and work with subjects was a challenge, as was deciding exactly what sorts of stories were appropriate to tell.

“The first meeting we had as a peer group, I was explaining what I wanted to do and what the movie might be, and asking who would want to participate,” he says. “Someone asked me ‘how do you know if there’s going to be a happy ending?’ And someone else immediately answered ‘that depends on us, doesn’t it?’ I’ll never forget that, because the person who said that was a woman named Lisa, who was supposed to be one of the main characters. She passed away before we started shooting.”

The three leads in The Stairs are people who are in some ways still dealing with the traumas and transgressions of the past. In addition to Marty, whose current outlook is relatively bright (he shows off his one-room apartment and pet cat with a hard-won sense of accomplishment), the principals are Greg Bell and Roxanne Smith, both of whom are working to help other drug users while also addressing their own ongoing dependencies. Greg, whose taciturn demeanour hints at a serious temper, is recovering from a violent run-in with police officers that has resulted in a legal situation. Roxanne, who has worked in the sex trade since her teens, tries to reconcile the dangerous aspects of her lifestyle with her responsibilities as a mother. What Gibson gets onscreen is the fragile, provisional nature of treatment programmes that are designed primarily to mitigate suffering and improve health by degrees. “The typical narrative is that you’re a drug user, you’re addicted, you go to rehab, and you’re cured,” says the director. “Reality is quite different. It doesn’t end there. In a way, it’s just where the story begins.”

Many of the stories that are shared in The Stairs are harrowing, never more so than when Roxanne relates a nightmarish tale of abduction and captivity that may test even the most jaded viewer’s responses. There is a hushed, attentive quality to the filmmaking, (the fluid, intuitive camerawork is by the director and Cam Woykin) and the verité style, with its lack of narration or exposition, hearkens back to great non-fiction practitioners like Allan King. Gibson also cites Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2013) and the works of Pedro Costa as inspirations, although he reserves his highest praise for a fellow Canadian: Alan Zweig, who is listed in the credits as an executive producer. “Alan’s film A Hard Name (2009) is the closest thing I’ve seen to a movie that has that sort of intimacy with its characters in a similar milieu,” he says. “Alan was involved from the beginning and he was there whenever I asked him to be. He also made three features in the time it took me to make this one.”

The prolonged shooting schedule for The Stairs could have resulted in a film of fragments, but the construction here is careful, and never more so than in the superbly realised final shot. Gibson says that he was guided throughout by the idea that his film could work in harmony with the sort of treatment he was documenting. “I thought that harm reduction was in the fabric of the movie, and its tenets are integral to how I made it. Being non-judgmental, having patience and acceptance. Or knowing that you can be challenged by a person’s behavior and still value them as somebody with feelings, who is worthy of dignity and respect.”

As a study of three people trying to break cycles of behaviour, The Stairs is compelling, but it’s also a work of local portraiture: long-time Torontonians will vividly recognise the east-end milieu known as Regent Park. And of course, to borrow a line from Luis Buñuel, the more specific a film is, the more likely it is that it can feel universal. “It’s about a specific neighbourhood in a specific city, but in my opinion, it really could be anywhere,” says Gibson. “Last summer in New York, I showed it as a work in progress for the Harm Reduction Coalition. There were maybe 20 people there with the same life experiences as Marty and Roxanne, and they all said they could relate to it, or that it actually was their lives.”

Source: POV Magazine

← BackNext →